Happy Native American Heritage Month 2024!

This is a new, condensed version of a book I originally wrote a half-century ago.

Technically, it’s a biographical “novelette.”

If any part is particulary interesting, click its heading to read the complete chapter.

Preface

When I met Eugene Standingbear in the mid 1970s, I was fresh out of Vietnam (where I’d been safely behind the lines fixing radio and radar systems in warplanes). Now back home and at loose ends, I spent some time with my folks… free room and board while I helped them with their little weekly newspaper on the prairie, in the tiny town of Keenesburg, Colorado.

I’d always had a knack for writing, so my favorite task was to write a feature story every week. It was surprising, the range of interesting people, pastimes, and backgrounds scattered among the small farming communities like Keenesburg, Hudson, Roggen, and Prospect Valley out there in Southeast Weld County.

Several people (including Mom) said I needed to talk to “the Chief”… an old, reclusive artist who took off from time to time in his big sedan, which rode low in the back, to attend Indian pow-wows, mostly up north among the Sioux tribe, or Lakota people.

And that’s how our paths crossed, forging my unlikely friendship with Eugene.

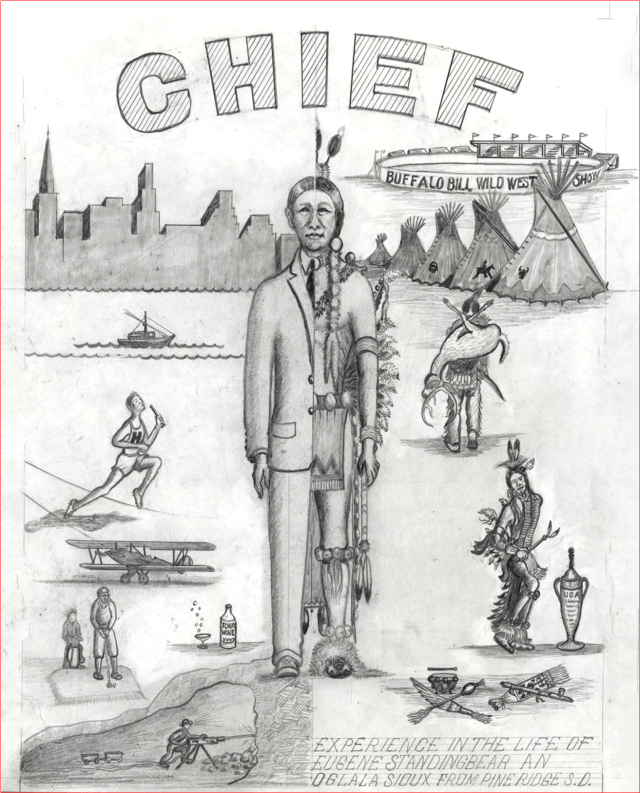

This is the condensed life story of Eugene George Standingbear as he told it to me in the 1970s. He’d had a colorful life…

- … from his childhood in Wild West Show arenas on both sides of the Atlantic, to his parts in wild west movies and TV shows…

- … from his life among the richest of the rich (riding in limousines, winning golf tournaments, and crossing paths with Presidents) to a decade on skid row (panhandling for enough loose change to buy a jug of wine)…

- … before finding peace at last, returning to his ancestral roots and capturing the old ways of his people in his sketches and paintings.

Eugene’s story is presented below in 12 bite-size pieces.

Introduction

01 “Chief”

Highlights: Hollywood and the High Life

02 Cowboys and Indians in Hollywood

03 Wealth and Royalty Among the Osage

Chronology of His Lakota People (1800s)

04 Strange, New World

Chronology of Eugene Standingbear

05 From the Wild West to the Reservation

06 Growing Up Among the Noble OmAHa

07 Indian Schools: ‘Kill the Indian, Preserve the Man’

08 Death of Chief American Horse / Sacred Instruments

09 Honky-Tonk, Rodeos, and Sports

10 Loose Ends and New Beginnings

11 Skid Row

12 Return to Heritage: Peace at Last

I hope you enjoy reading Eugene’s story as much as I enjoyed learning it!….

(PS – During Eugene’s lifetime, most people (including Eugene) referred to his people as “Indians.” Eugene referred to homeless alcoholics like himself as “winos.” These terms are offensive to some people, but I use them in the story to keep the mood of the times. No disrespect intended.)

>>>>———————————>

Introduction

01 — Chief

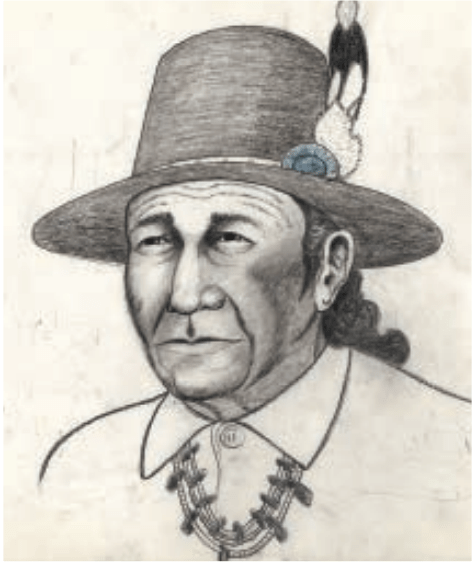

I started writing my first book in the 1970s. It was the life story of my friend Eugene George Standingbear, a remarkable Native American from the Lakota (Oglalla Sioux) tribe in South Dakota. It was roughly written and never got published, so a few years ago I polished it up a bit and published it here on NobleSavageWorld. Eugene was in his 70s when I met him, a few years before his death. I’m in my 70s now, so maybe we’ll reconnect one of these days soon. (Afterlife is kind of my thing, after all. 🙂 )

Eugene was caught between two worlds, as told by Alisa Zahller at the History Colorado Center in Denver, who received some 300 of Eugene’s paintings and sketches after he died and included him in the RACE: Are We So Different? exhibit in 2014. (More about that at the end of the story.)

By the time I’d met Eugene, he’d reconciled his life between those two worlds—his Lakota heritage and the EuroAmerica (the ‘white man’s world’) he was born into—but getting to that place of peace involved a lot of ups and downs and some pretty incredible synchronicities. (He was a charming, talented fellow who was always in the right place at the right time… a sort of smart, healthy Native American version of Forrest Gump,)

And the title “Chief?”

- Eugene Standingbear was never a leader of his people—a chief—though there were early signs (his athletic prowess, his artistic abilities, his charisma, the influences of his mother and his Uncle White Bull, and the chiefs in his family line that include his famous father Luther Standing Bear …) to indicate that he might have become a Lakota chief, had he been inclined. But his destiny and restless nature carried him away from his people and into American society… for better or worse.

- On the other hand, white people often called him “Chief.”

>>>>———————————>

Highlights

02 — Cowboys and Indians in Hollywood

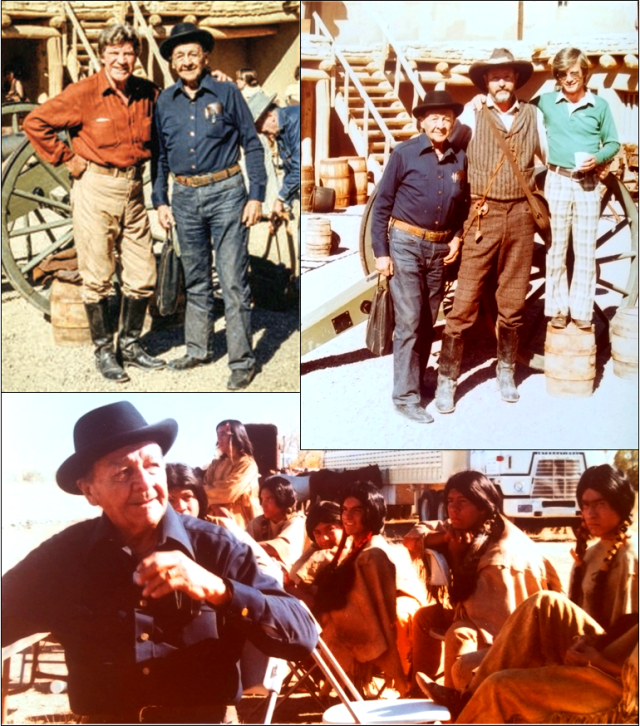

Grizzly Adams. In the autumn of 1977, shortly after I met him, Eugene was called to play the part of an old Lakota shaman in an episode of the popular Grizzly Adams TV show, appropriately titled, “A Bear’s Life,” filmed in the Uinta National Forest in Utah.

Eugene got to sing an authentic Lakota song during the episode, though he was a little embarrassed by the strange costume he had to wear. “It made me feel like an Indian clown,” he told me.

The Chisholms. The next year (1978) he acted in the seventh episode (“The Siege”) of the highly popular mini-series, The Chisholms, which began airing in 1979 and ended in 1980, the year Eugene died. I met him out on location for the filming, Bent’s Old Fort near La Junta, Colorado, and took some pictures between takes:

Again, he said, the Indian costumes weren’t portrayed accurately, but he enjoyed getting to know the cast and crew, and he got to work with Indian technical advisor George American Horse to set up an authentic healing ceremony for the episode.

Pony Express. Eugene’s introduction to Hollywood happened a half-century earlier, in 1925. Every summer a group of Lakota left the Pine Ridge reservation to entertain at the Cheyenne Frontier Days celebration in Wyoming. Word spread quickly that year that a Hollywood crew would be filming a western movie in Cheyenne and would need Indian extras. It stirred a lot of excitement.

On the big day, Eugene joined several hundred men and women to load trunks, musical equipment, teepee poles, and rawhide teepee walls onto the trucks, climbed aboard, and off they went. Arriving in Cheyenne that evening, they set up camp over the hill from the film location.

The next morning a film rep came to camp, gathered everyone around, and said he was looking for someone to play a fight scene with the lead character. Eugene didn’t hesitate. “I’ll do it!”

The film rep walked him over the hill to location—the prop of a frontier town.

As they approached the town of propped-up building fronts, the rep filled Eugene in about the movie and his part in one of the closing scenes. The movie was Pony Express, with Wallace Beery, directed by James Cruze. As part of the plot, a Lakota band had abducted a young, Shirley-Temple-ish girl, and Wallace Beery loved the cute little filly like a daughter, so he was fighting mad… killing Indians left and right… anyone he could get hold of. Eugene would fight with Wallace Beery at the end of the movie.

He stripped down to breech cloth and moccasins and put on a wig with long, black braids. The assistant director told Eugene he’d be carrying a tomahawk and torch and would try to set Beery’s blacksmith shop on fire. Eugene would enter through the alleyway from the rear of the building prop while Beery would emerge from the front door, come around the corner of his shop, and catch Eugene red-handed.

Running through rehearsal, Beery and Standingbear met near the alley. Beery grabbed Eugene loosely by the throat while a camera stood nearby for a close-up shot.

“Indian, where is that girl?!” Beery shouted while choking Eugene lightly, bending him backward over a hitching rail, then throwing him down on a mattress the crew had buried a few inches beneath the dirt to break the fall.

The assistant director barked through his megaphone, “That’s good! This is going to be a take. Places!”

Eugene climbed to his feet, dusted himself off, and went back behind the building prop. “Action!”

This time Beery was amped up. He grabbed Eugene by the throat and squeezed hard until he could barely breathe. Beery roared, “You gawdammed Indian! Where is that child?! Where is she, you filthy savage?!” (Fortunately it was a silent movie.)

Eugene croaked, “Mr Beery, Mr Beery, you’re choking me.” Oblivious, Beery threw Eugene down at the mattress as hard as he could. Eugene’s head hit the ground behind the mattress and he saw stars.

“Cut! Good! Put it in the can.”

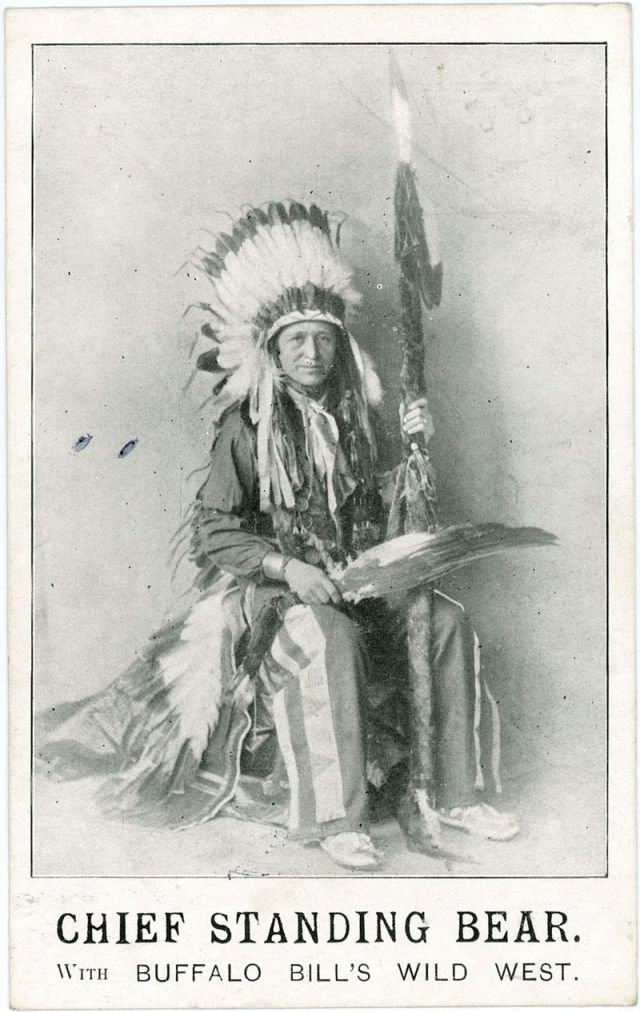

Luther Standing Bear. In the 1930s Eugene was living in Pawhuska, Oklahoma, married to Mary Lookout, daughter of Fred Lookout, Principal Chief of the Osage tribe. His dad, Luther Standing Bear, was living in Huntington Park just a few miles from Hollywood, presiding over the American Indian Progressive Association, writing books and lecturing on the need to keep Native American heritage alive, and working as technical advisor for Indian movie sets.

The Osage were the richest-per-capita people in the world at the time because of oil discovered on their land in 1897, so Eugene was living a Gatsby life—traveling the country in limousines and competing in golf tournaments (often winning). He hadn’t seen much of his father since he was a little boy, so his wife Mary and the Lookout family decided it was high time Eugene paid his dad a visit.

Eugene hopped on a train to Los Angeles with a stopover in Phoenix, Arizona. A golf pro had built a new golf course in Phoenix and had invited Indian golf champ Eugene Standingbear to play an exhibition match to publicize the new venture.

When he met Eugene at the station, the pro asked if he had a good picture of himself for the local newspaper to publish before the tournament, but the only good picture Eugene brought along was this picture of his father. “Perfect,” said the pro.

Eugene showed up for the match in a beaded Lakota outfit. To please the spectators, he danced between shots for good fortune and delivered a war victory whoop after completing each hole.

Next day he caught a train to Los Angeles, then a taxi to his father’s house in Huntington Park. Luther Standing Bear welcomed his son with a grim look on his face, making Eugene a little nervous, and led him to the study. He reached across his desk, grabbed a copy of the Phoenix newspaper with the picture of himself in Lakota Chief regalia, and held it in front of Eugene with a frown. Then he broke into a laugh, shook his head, and said in his deep, gruff voice, “I didn’t know I played golf.”

They spent a week touring southern California in Luther’s brand-new Buick, meeting his friends, playing billiards, shooting bow and arrow, and talking about their lives. Eugene was impressed by his father’s skill with bow and arrow. He told Eugene that one of his pastimes was competing (and winning) against the Japanese professional archers who toured occasionally through southern California.

During his visit, Luther introduced his son to two of his close friends—Iron Eyes Cody and William S Hart.

William S Hart is often remembered as the “storybook” cowboy and the original big-screen cowboy, always playing a noble-savage character who had to be tough, sometimes violent, in his quest to spread peace and good will in the Wild West.

Hart had a mansion (now a museum) on a big spread in the Santa Clarita Valley north of LA with a big herd of spotted horses cared for by a dozen Plains Indian ranch hands. He often hosted big gatherings at his home that he’d decorated with Native American blankets, artwork, and artifacts, gun cases filled with pistols and rifles, and an in-home movie theater.

At one gathering he’d arranged for Luther and Eugene to perform a traditional Lakota dance. Luther beat a huge, wooden floor drum while his son performed a slow war dance, a chief’s dance, and a fast dance before a packed audience.

Iron Eyes Cody. Hollywood cowboys and Indians were all the rage in 1930s America, and Cody was a familiar face on the big screen. Over the years he appeared in more than 200 movies and 100 TV shows dressed in Native American costumes.

He wasn’t really a Native American, though. He was born in Louisiana as Oscar DeCorti, son of Italian-Sicilian immigrants. His friend Luther Standing Bear had given him the Indian name Iron Eyes Cody because of his silver-colored eyes.

Cody helped to further the lives and careers of many Indian extras, who used his cottage on Gower Street as a home base. He closely monitored all the studio projects and was aware of upcoming parts for Indian actors and extras months in advance.

Eugene was enthralled by the glitz of Hollywood westerns and postponed his trip home to Oklahoma. He moved into the Gower Street cottage for a few months, and began working in the movie business.

His first assignment was to sit in a sound booth, listen to a film clip of an Indian chief speaking English, and do a voice-over in Lakota. When the film rolled, Eugene was surprised and a little in awe. The Indian chief was none other than his new friend Iron Eyes Cody.

Back at the cottage, Eugene told the old, grizzled Lakota cook about his good luck—50 bucks at the pay window—and the cook warned him to keep it quiet. The other guys would be jealous.

Well… when the truth did come out (leaked by the cook, no less), all hell broke loose. When Iron Eyes threw a party after the screening of the film, his brothers Frank and Joe DeCorti started boasting, “Hey, ol’ Oscar can talk Indian as well as any Indian!”

The cook had had a few too many drinks and grumbled, “Hell, that ain’t Oscar, that’s Eugene talking. He was dubbed in.”

One of the DeCorti boys said he was lyin’, and fists started flyin’… just like in the movies.

Chase scenes. When the studios needed good riders for chase scenes, their first call was often to the Gower Street cottage. Another bread-and-butter day for the Indian extras. They’d show up on location, get painted red to look like ‘real Injuns,’ and get 15 dollars richer at the pay window at the end of the day. Here’s a typical day on the set:

- Everyone waits near their horses until the director barks, “Renegades!” The actors put on buckskin leggings, big renegade hats and breech cloths, mount up, and storm past the camera chasing a stage coach or supply train.

- “Cut! Okay! Indians!”

- The actors change into Indian war costumes and make another full-speed pass.

- “Cut! Cavalry!”

- The actors replace the Indian clothes with blue army outfits to storm past the camera for a final sequence….

A few weeks later, during the premiere, a series of war victory whoops would fill the theater from the front row as the Indian extras watched themselves flash across the screen three times: a dozen renegades being chased by a dozen Indians, in turn being chased by a dozen mounted soldiers swinging sabers, firing army pistols, blowing bugles, and waving flags.

Indians die laughing. Indian extras bragged and joked about how often they died in the movies. Directors were miffed when their cameras panned bodies strewn about after a massacre scene, and many of the “dead” Indians had broad grins across their faces.

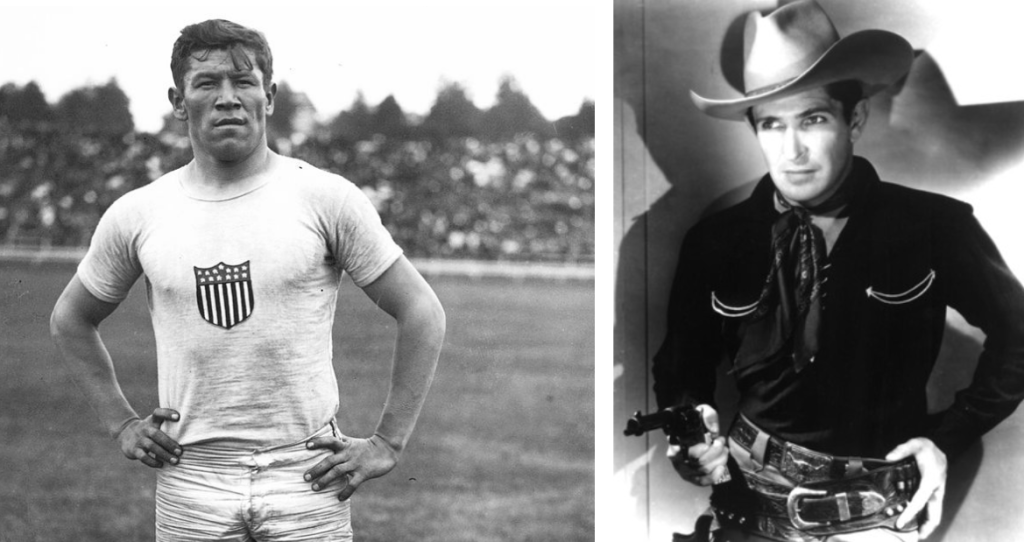

Jim Thorpe and Bob Steele. Eugene traveled a lot across America in the 1930s and 40s, and when passing through southern California he’d sometimes stop in Hollywood to do some film work, where he befriended Jim Thorpe, the famous Native American athlete, actor, and humanitarian from the Sac and Fox tribe.

In one movie, Thorpe and Standingbear were playing bit parts opposite then-popular cowboy star Bob Steele. In the script, the wiry, 5’5” Steele was killing savage Indians left and right.

In one scene, Steele was supposed to wipe out seven knife-wielding Indians in a single brawl. To have a little fun and amuse the crew, Thorpe and Standingbear called the other five warriors together for a brief powwow. When the director barked, “Action!” the seven Indians formed a circle around Bob Steele and moved in. Thorpe grabbed the little man around the knees and set him down on the ground as the other Indians grabbed and arm or a leg and started hacking and chopping the air around Steele’s body with their rubber knives and tomahawks.

“Stop! Stop! Cut! Cut!” shrieked the director while the crew and spectators all cracked up. Everyone enjoyed the diversion… well, not quite everyone. The director was fuming and cussing about wasted film, while Bob Steele was still stretched out on the ground like a coyote, struggling to get free.

>>>>———————————>

03 Wealth and Royalty Among the Osage

Eugene graduated from Haskell Indian College in Lawrence, Kansas, in 1926, the year that a massive stadium was erected at the school—the only sports stadium in the entire Midwest with overhead lighting. It was funded and built entirely by Native Americans. It was a big deal.

An even bigger deal (for Eugene, at least) turned out to be his casual friendship with fellow student Freddie B. Lookout, the grandson of Fred Lookout, Principal Chief of the oil-rich Osage tribe.

During lunch, Eugene was invited to sit with Freddie and his father, Charlie Lookout, who’d driven from Oklahoma in one of the family’s brand-new limousines to attend his son’s graduation. Charlie invited Eugene to spend the summer on the Osage reservation as Freddie B’s companion, and Eugene gladly accepted.

Within days of arriving in Oklahoma, Eugene met Freddie’s pretty sister Mary, and the two soon decided to get married. Well… to be more accurate, it was decided—by a council of tribal elders—that the two should be married, and by Native American custom, there was no debate.

If Eugene’s life were a movie plot, that marriage would be the inciting incident, or turning point, in his life. And it happened at a time when the Osage tribe was embroiled in an inciting incident of its own.

When oil had been discovered in Osage County in 1897, tribal chief Jim Bigheart, or “Big Jim,” had lobbied successfully with the government to make sure the mineral rights remained in the possession of the Osage people. Thanks to Jim Bigheart’s life mission to care for and to protect the well-being of his people in the new America, the Osage became the richest per-capita community in the world. After his death, though, the gift became something of a curse for a while.

In the 1920s, a “reign of terror” befell the Osage people as white treasure-seekers descended like locusts, devising ways to take their oil money, including inter-marriage, murder, and a combination of the two. More than 60 murders of full-blood Osage people went mostly unsolved, some perpetrated blatantly by white ranchers, businessmen, and opportunists in the area (especially around the reservation town of Fairfax). Jesse James, the Daltons, the Doolins, the Martins, Al Spencer, Frank Nash, Henry Wells, Belle Starr, Cattle Annie, and other notorious outlaws moved to or through Osage County to grab their share of the loot.

Most of the bloodshed and mayhem came to an end in 1926, when the young FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation) began unraveling its first big case: the Osage murders. It’s also the year that Fred Lookout, known for wisdom, integrity and faithfulness, began his 23-year stint as principal chief of the tribe, and peace and prosperity started to come together, at last, for the Osage people.

1926 is also the year that Eugene graduated from college and got married, and when “Standingbear” and “Standing Bear” became prominent names among the Osage.

Not long after the wedding, a bank officer told Eugene George Standing Bear that he couldn’t open an account with two last names, so from that point on, for the rest of his life, he called himself Eugene George Standingbear.

Eugene and Mary had a son, George Eugene Standingbear, in 1929, who would later marry Barbara Wright and together raise four children: Geoffrey Mongrain, Eugene Sean, Patrick Spencer, and Margaret Mary Rebecca (Meg) Standingbear.

Over the years, family members would begin to reclaim the original surname, and today (2018) Geoffrey M Standing Bear is Principal Chief of the Osage.

Eugene began to win golf tournaments around the country. He started traveling by car (family limousines) or by train (rented coach cars) to big events involving US Presidents (think Calvin Coolidge).

But the most fun he had, by far, was fulfilling his lifelong dream: to fly like an eagle. He and pilot Jess Smith became co-owners of an OX-5 biplane, and without formal training Eugene quickly learned how to pilot the popular craft. The two men started barnstorming towns, landing in a nearby field, and taking passengers on short flights at a dollar a pop.

Eugene learned the trick of wing-walking—hold on tight!—and the art of doing spins and loop de loops.

Oilman Frank Phillips, a good friend of the tribe, was aware of Eugene’s love of flying and invited him to be “Standingbear, pilot of Gray Eagle,” or Standingbear, pilot of Eagle Chief” (two of the Indian names the tribe had bestowed on Phillips).

To become Phillips’ pilot, Eugene would have to get trained on multi-engine aircraft, but his mother-in-law Julia Lookout put her foot down. “You’re a family man, Eugene, and flying is too dangerous”… and by tribal law throughout the States, the tribal family made the big decisions that involved the purse strings.

As a consolation prize, Eugene was allowed to take single-engine pilot training at Garland Flight School, 60 miles away in Tulsa, where he immediately developed a bristly practical-joke relationship with the scrappy 6’3” flight instructor, Captain McLaughlin.

The captain would sneak into the barracks early mornings while all the students were sleeping and tip Eugene’s bed until “the Chief” tumbled to the floor. He’d jump to his feet and they’d scuffle, and Eugene typically ended up with the most bumps and bruises.

Eugene held a trump card, though. No one at the school knew about his previous flying experience except himself and the school superintendant. McLaughlin and everyone else thought Eugene was just a quick learner.

So, for his first solo flight, Eugene sat in the pilot seat, props spinning, engine roaring, as Captain McLaughlin walked up and shouted some last-minute instructions up to him. “Okay, Chief, take ‘er up nice and easy, make a turn, and bring ‘er in pretty!”

Eugene nodded, taxied to the end of the runway, turned around, and gunned it. He brought the plane 10 feet off the ground and headed straight for the hangar and his wide-eyed instructor. About 100 feet from McLaughlin, he pulled back on the stick and shot up like a rocket. It was a good little stunt ship, a Great Lakes Trainer. He spiraled upward until he had enough altitude for some maneuvers, then flew a tightened loop to lose some altitude, made a turn-and-a-half spin at the end of the field to get even lower, and then fishtailed in for a shortstop landing.

As Eugene taxied slowly up to the hangar and climbed out of the cockpit, McLaughlin was furious. “That’s the stupidest gawdammed thing I ever saw! Soloing like that’ll kill ya!….”

On another occasion, Eugene was practicing spins, in which the plane spirals downward like a maple leaf, faster and faster, until the pilot pushes the stick forward (during right-hand spins) or pulls it back (during left-hand spins) and the rudder stops the spin, pulling the plane onto a level flight path. On this occasion (a right-hand spin), he pushed the stick all the way forward, and nothing happened

The plane continued to spin faster and faster, the tail began to shake, and the young flight instructor—a former air force lieutenant sitting in the front seat—tapped his head to signal, Hands off the controls; I’ll take over.

Eugene watched helplessly as the stick swung forward and back, forward and back, with no effect. The plane kept spinning faster and shaking more violently as they plunged toward the ground.

By instinct, Eugene grabbed the stick in an iron grip with both hands and shoved it so hard that he dented the aluminum backing on the front seat… and suddenly the plane snapped out of the spin. He gaped out over a cottonwood tree and saw the veins of its leaves as the plane pulled into a level flight 40 feet above the ground.

Meanwhile the mechanics and pilots at the airstrip had gathered to watch the deadly spin beyond the horizon. A couple of guys ran to call for meat wagon (ambulance).

There was a stunned silence as the plane climbed slowly over the horizon, and Eugene cut the throttle to glide silently onto the runway. Then he let loose an ear-splitting war victory whoop, which might have been the only sound at the Garland school at the moment.

The young lieutenant turned his head slowly around, his face pale as a ghost, and gaped through eyes as big as dollars at the Indian who’d just saved his life.

An inspection of the plane discovered that the rudder had been aligned straight back instead of tilting it to compensate for the turn of the propeller. If might have been a practical joke by Captain McLaughlin or, more likely, just a “mechanic error.” Anyway, that was the school’s official explanation.: Mechanic error.

Eugene quit flying shortly after that, not because of the harrowing experience but because of the Great Depression, which put an end to lavish living among the Osage… and just about everyone else in America.

>>>>———————————>

Chronology of His Lakota People (1800s)

04 Strange, New World

Here are some of the key events leading up to and through the 19th Century that were part of the “inciting incident” for the Native American people… turning points that changed their lives forever.

1500s. HORSES were brought over to America by Spanish explorers on their sailing ships. The horses had to be small for transatlantic travel. As decades passed, the horses proliferated, and by 1750, many of the Plains tribes had adopted the small “Indian ponies” into their culture. Buffalo hunts grew to legendary proportions. Capturing horses from other clans or from the wild became a major coup, and counting coup was a mark of honor among young men.

1600s. FIREARMS (guns) were invented in China around the year 1000, started to become prevalent in Europe in the 1300s, were first used in battle in the 1500s, and were brought to America by early European settlers starting in the 1600s. Like horses, guns slowly began to reshape the lives of Native Americans in the coming centuries.

1730. The Cheyenne tribe introduced Lakota clans to horses. The Cheyenne lived mostly in what’s now Colorado, Wyoming, and southern Montana, while the Lakota lived mostly in Minnesota and the Dakotas east of the Missouri River, and horses made it easier and more exciting to follow the buffalo migrations. Small Lakota groups crossed the Missouri westward to explore and sometimes to raid other clans.

1765. The first “Lakota Chief Standing Bear” on record (no known relation) discovered the Black Hills while leading a raiding party. The Cheyenne were occupying the Black Hills at the time, but it was at the eastern fringe of their large domain, not easily protected.

1776. The Lakota defeated the Cheyenne clans living around the Black Hills, pushed them out to Powder River country, and claimed the Black Hills as their own. The area would remain sacred to both tribes, as well as to the Arikara, Crow, Kiowa, and Pawnee.

This was also the year the United States became a nation and soon went about adopting a constitution.

1830. Tribes (starting in the Deep South) began to walk “the TRAIL OF TEARS” when the Indian Removal Act began forcing entire Native American tribes off their homelands and marching them onto reservations in order to make room for the rapid spread of white culture.

1851. The western US still had a lot of wide-open space. Under the first Fort Laramie Treaty, Uncle Sam, feeling generous and hopeful, set aside a vast land as INDIAN TERRITORY for the tribes inhabiting the region (Lakota, Arapahoe, Cheyenne, Crow, Assiniboine, Arikara, Hidatsa, and Mandan) with the condition that the tribes would get along with each other and allow non-Indians to pass through peacefully. In return they’d get financial and military support from Uncle Sam. A noble idea, but…

As the map illustrates, peace was not to be, and the Indian Territory would be split into pieces. Here’s what happened, in a nutshell:

- Tribes kept pushing each other off their allotted land.

- Gold was discovered in the Black Hills, bringing a flood of miners and settlers… and Custer’s army.

- Native Americans were understandably outraged by this locust plague of white people.

- Lots of battles broke out, big and small.

Then, a massive battle exploded back east.

1863. When the Civil War broke out along the eastern seaboard, and Native elders heard stories of 50,000 white soldiers dying in one battle alone (Gettysburg), a foreboding descended over the Plains Indians. This was a whole new level of savagery, and it became clear that life as they knew it was coming to an end.

1879–. The Great Sioux War, including Custer’s last stand, was, in fact, the Native Americans’ last stand as traditionally free communities. Uncle Sam’s aim now was to get all the Indians onto reservations and galvanize them with a protective layer of white culture against the rigors of this strange, often brutal new world.

Eugene’s dad, Luther Standing Bear, would later write that attending Indian schools like Carlisle and Haskell was the new version of counting coup.

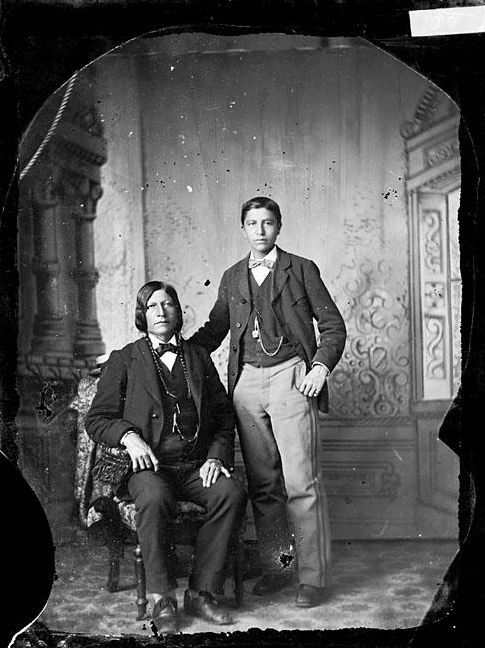

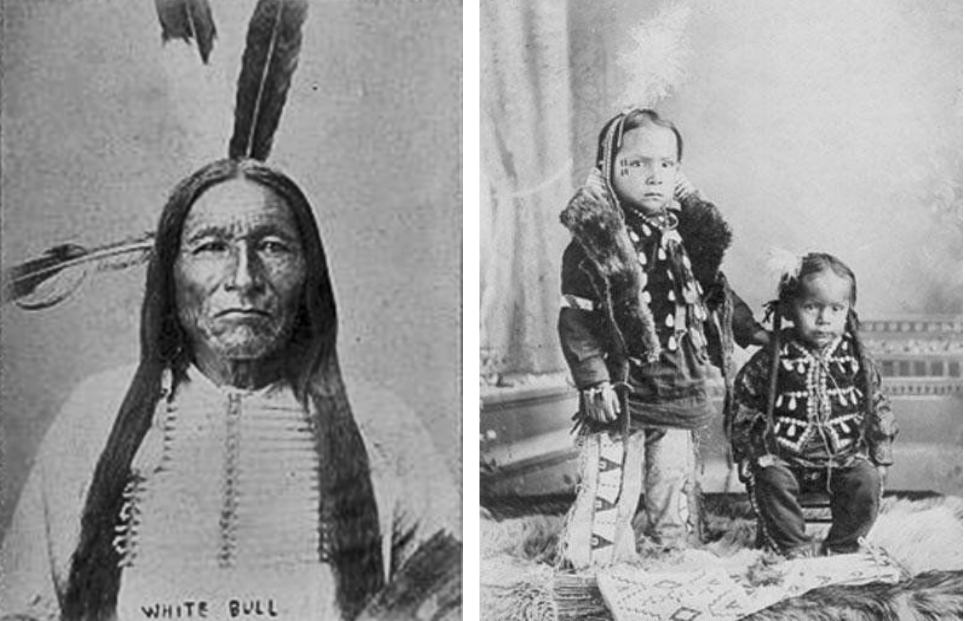

Out with the old, in with the new. Finally, this is Eugene’s mom, Laura (Cloud Shield) Standing Bear and her first-born son posing (probably in 1903) during an international tour of the Buffalo Bill Wild West show. The boy—Eugene’s older brother—died in childhood from a disease picked up in Europe.

The Lakota and other indigenous peoples were well acquainted with white culture by now, but Uncle Sam continued with his relentless policy to forge them into new Americans, mostly through Indian Schools.

>>>>———————————>

Chronology of Eugene Standingbear

05 From the Wild West to the Reservation

When I met Eugene Standingbear around 1977, a few years before his death, his most vivid childhood memories included riding with his mom on a steamship to Europe (possibly in 1908), in the Miller Brothers 101 Wild West Show. The Lakota boys were enchanted by the masts and rigging lines. Eugene was too young to climb, but he watched in awe (and the moms watched nervously) as older kids scrambled up high above the deck and did brave antics.

Eugene was born on March 7, 1906, to Luther Standing Bear and Laura (Cloud Shield) Standing Bear, two prominent members of the Buffalo Bill Wild West show. Most Native Americans were considered non-citizens at the time and were confined to reservations. Once they were galvanized (coated with white culture, usually by attending Indian schools), many were granted citizenship status.

Luther became a citizen in 1907, allowing him to move off the reservation, leaving his wife Laura and son Eugene on the Pine Ridge reservation. Laura would continue traveling with the wild west shows, bringing Eugene along on one trip overseas in 1908, while Luther made it his mission to help his people find a noble place in the new America.

By 1908, with international tensions building in Europe leading toward the first world war, and with the coming of motion pictures, the many wild west shows (1870-1920), which had been all the rage, were now losing their luster… so Laura and her son Eugene eventually returned home to the Rosebud and Pine Ridge reservations in South Dakota.

Uncle White Bull. While Laura was finding her way as a single mom, she often left Eugene with the family of her brother, Eugene’s Uncle White Bull #2, a full-blood Lakota who lived with his wife Emma and their two sons, Levi and Martin, at Porcupine district on the Pine Ridge reservation. Porcupine station had a post office, general store, and Indian ration house that received surplus army supplies (especially food, blankets, clothes, and hobnail shoes mass-produced for the first world war) that were distributed to reservation families who needed them. The store was in a valley beside a creek between ridges topped with pine and cedar trees.

White Bull sometimes told Eugene and his two cousins Levi and Martin about the spirits he could see from the corners of his eyes. “They move very fast, and by the time you turn your head to look at them, they’re gone.” He could speak to the spirits, and they sometimes answered silently in his mind. Or they might answer through the wind or through the actions or sounds of birds and animals.

White Bull never had the opportunity or desire to learn English, and he didn’t suffer the strange rites of Christianity, like getting on your knees and humbling yourself. White Bull was a warrior in the Lakota tradition. He knelt to no man. One of his pastimes was to have his son, Levi, walk around him slowly in a big circle while he fired arrows accurately between the boy’s feet. Naturally, White Bull never touched alcohol. His mind, like his aim and his arrows, was always sharp.

The fact that kids across the reservation were being sent to Indian Schools (especially Christian Indian schools like the one at Santee, Nebraska), filled him with apprehension, and he refused to let Levi and Martin be sent away.

Laura had been baptized and indoctrinated into Christianity at Carlisle Indian school and made sure that her son Eugene was baptized too, and that he would attend Indian schools when the time was right, but for now little Eugene got the chance to steep himself in Lakota tradition. (On one occasion, Laura and her sister-in-law Emma snuck a Catholic priest into the home to baptize Levi and Martin, but when White Bull found out later, he was furious. He took the two boys aside and vigorously scrubbed off the “bad magic” with soap and water.)

Throughout the year the families would gather on special occasions in one of the rough and sturdy lodges—either a longhouse building or one of the large, roundish, six-sided structures, all made with logs—to treat neighboring districts to an evening of feasting and dancing. Eugene admired how White Bull and his wife Emma prepared for the celebration, dressed up in their finest dancing clothes, and readied their sons Levi and Martin. First thing in the morning, Aunt White Bull started a fire under a large kettle of dried meat with wild turnips to simmer all morning for the potluck celebration and dance, which would begin around 2pm.

Meanwhile the couple got dressed up. She put on a broad-cloth dress decorated with elk teeth (only the front teeth of bull elk), and a wide concho belt with string tapering down the side of the hips. A wide ribbon with a large bow tied behind her neck had two long streamers hanging down. She wore broadcloth leggings and beaded moccasins. Eugene thought she was stunning… beautiful.

Uncle White Bull put on an Indian calico shirt and a leather belt to hold up his broadcloth loincloth and plain buckskin leggings, with short fringes down the sides. He wore a braided sash of pretty designs over his shirt and a braided strip around his waist. During the day he’d wear his wide-brimmed reservation hat with high, tapering crown. Sometimes he’d tie a handkerchief around the hat and tuck in an eagle feather with its black tip pointing straight back. In his hand he carried his long pipe in his tobacco pouch.

Then Uncle and Aunt White Bull would help each other with final preparations. She would braid his hair using tallow grease melted down with fragrant herbs, maybe sage or peppermint. Then he had his wife sit down so he could stroke her hair into good shape with a porcupine-tail comb. He’d part it exactly in the center of her head, then apply face paint made from berry dyes and clays mixed with tallow to form a paste. The desired effect included red cheeks, a red part in her hair, and specific markings on her chin and forehead.

Traditionally, each person had his or her own paint and colors and designs, and upon death, a holy man would decorate the body appropriately so they could take their colors along to the next life. The family would then give the holy man gifts of robes, headwear, or even a horse.

Levi and Martin would strip and put on beaded moccasins with fur around the ankles, then bells above the ankles and below the knees. A leather belt held up the loincloth, front and back, along with a decorated feather bustle in back, and two trailing strands with decorative feathers. On the side of the belt were strips of leather hanging down nearly to the ground, tapered to a point and decorated with large, shiny silver or nickel studs. The boys’ chests would be covered by a bone breastplate or beaded vest or yoke of fine fur such as otter with small mirrors sewn on. The boys’ long hair, either braided or hanging loose, spilled out over a beaded neck-choker. The head piece was made of porcupine longhair and deer tail hair and bore the ultimate Plains Indian symbol: two eagle feathers in the center pointing straight up in reverence to the eagle, the highest and sharpest of creatures on Earth. White Bull carefully painted each of his son’s unique, personal designs on their faces and torsos. Levi wore brass arm bands and bracelets and carried a rawhide gourd with an eagle feather tied to the tip.

After a couple of years, the White Bull family started dressing Eugene up for these tribal celebrations too.

Like most of the other old full-bloods, Uncle White Bull was a warrior, not a holy man. He had an eagle-wing fan that he sometimes carried and used in dances to fan himself, unlike the holy men themselves, who had their eagle-wing fans with them much of the time to help guide the flow of spiritual energy in the tribe. White Bull’s most important and sacred belongings—his fan, his double-trail war bonnet, his beaded buckskin war shirt and leggings and moccasins—he carried with him to celebrations in two large rawhide bags, like suitcases. The leggings were beautifully beaded with long fringes. When he danced he kept his knees high and his elbows back as he leaned forward. Eugene thought he was a magnificent sight. White Bull didn’t want to taint the dignity of his dancing clothes with bells, so he let the other men keep the beat. Dancers traditionally wore deer-hoof clackers, or “deer toes,” which cast a mellow, mystical aura over a crowded dance floor. The more modern bells were louder, brighter, and produced a more intense, almost intrusive atmosphere… but they could certainly keep the beat.

So, the celebration started that day around 2 pm with a speech or two by tribal leaders, followed by the chief’s song. Then many different songs were sung, and the dancing went into full swing. Throughout the afternoon the dancing would be interrupted by giveaway ceremonies, when gifts would be given to visitors and friends. It was a mark of honor to give someone a gift, and an honor to receive it.

Meanwhile, back to the evening of the feast on Pine Ridge, the food had been heating up outside all afternoon, and after a couple of hours of dancing it was brought in. Two of the best fancy dancers were selected to do the pot dance to introduce the first course: Pispiza (prairie dog) stew. Each dancer was given a forked willow stick. As a special song was sung, both dancers would dip their willow sticks into the pot and come out with a prairie dog head, which they’d give to the oldest man, who had the seat of honor in the front row. Sometimes it was uncertain who was oldest, since no one had kept track of birth dates in the early 1800s, so the special song might be sung several times while prairie dog heads were served to several old men in the front row. Then the music stopped and everyone joined the feast of many courses using their own plates and cups, which they’d brought along to the celebration.

After the feast, some people returned to their tents to lie down and rest before the dancing, which would continue until sunrise. The most grueling part of the evening for the men was the longdance. The dancers didn’t know when the longdance would begin—the head singer decided—but once it started, the dancers had to keep dancing. Sometimes the doors of the lodge would be bolted so no one could enter or escape during the longdance. Sometimes Eugene would get so exhausted that he wanted to drop… but he kept on dancing. If someone quit dancing and sat down, the whip man, or sergeant at arms, would come over and give him a few hard licks with his bone-handle whip with braided wrist loop and rawhide strand, or “fall.” The intent was not to punish or seriously hurt the young man, but to bring shame—a loss of honor and respect. It was important to keep dancing in order to show your manhood and to protect the family reputation. There was a lot of honor tied up in the war dance. Most of the dancers knew most of the songs, and it was important to make the right moves and to stop on the right beat, lest you earn lots of snickering up blanket sleeves. Visitors from other tribes who didn’t know a song would sit out, and the whip man didn’t bother them. The long dance wouldn’t end until someone finally gave away a cow or a horse to stop it, but no one made that gesture until late into the dance.

Over the years Eugene won several awards for his excellent dancing skills.

Eugene recalled that many of the men in his tribe were like his uncle White Bull… men of honor who respected the ways of their people. They were honest, forthright, patient, dependable, and proud of their perseverance.

Later on, Eugene would leave the reservation and find that living in a modern society was different. Noble values didn’t play such an important role. He’d say, “I met a lot of big shots, but usually you could dot that o.”

>>>>———————————>

06 Growing Up Among the Noble OmAHa

In the course of her travels Laura met up with her old Carlisle classmate Levi Levering, a prominent member of the OmAHa tribe, whose reservation of rich farmland sat along the banks of the Missouri River in Nebraska.

Levi had earned a reputation as “a man of excellent character” at Carlisle. Graduating in 1891, he became prominent back home in the town of Macy, Nebraska, on the OmAHa reservation. Levi married Laura in 1914, and Eugene spent the rest of his childhood living among the OmAHa people and attending various boarding schools, especially Pipestone (Minnesota) and Santee (Nebraska). Levi Levering was a strong advocate of Native Americans integrating themselves into white culture by going to school, while he also worked hard to preserve the beliefs and traditions of his people.

In 1914, as Laura and her son Eugene began living on the OmAHa reservation, she found a teaching job, and Eugene’s new stepfather worked as chief clerk at the Indian Agency.

With good corn land, the OmAHa people were a relatively wealthy tribe. The Leverings were especially well off because of Levi’s chief clerk position. The family had a white, T-shaped, two-story frame house with five bedrooms, a spacious front room, a huge crystal chandelier, a black, coal-burning stove and even a phonograph—the old Edison model with stovepipe horn and cylindrical records. No one else on the reservation had a phonograph.

Levi was prominent in the Presbyterian church, and on Sundays the Levering boys dressed up in knicker suits, hightop, shiny shoes, and Buster Brown hats. The Leverings’ affluence made the more traditional families a little stand-offish. They were especially wary of the two Lakota outsiders—Levi’s new wife Laura and her son Eugene.

At a dance one evening, Laura was sitting in the back row watching the dancers, when Eugene entered the lodge quietly and sat beside her. She noticed he had a bruise on his face.

Suddenly the dancing stopped and the crowd stirred as three men carried a whimpering, beat-up boy to the front of the lodge.

“I did that,” Eugene whispered to his mom.

Laura looked alarmed and whispered, “Shush-sh, don’t let them know you did it.”

Eugene had been complaining lately that some of the boys often said, “Shuh-uh Zhing-uh” (There’s that Lakota boy). They liked to gang up on him and push him around. She’d told him, “If it gets too rough, use a stick.” He’d taken her advice that evening.

Rattlesnakes and bucking broncs. Eventually he was accepted by his new tribal family, and he liked to spend his spare time with some of the OmAHa boys riding bareback on the wilder horses owned by local farmers… or sometimes adventuring to Snake Hill.

Snake Hill was a barren, massive butte where rattlesnakes coiled lazily on the sun-baked sandstone. As the boys approached, a few shaking tails hissed a warning that quickly grew to a sibilant clamor as alarm spread among the vast community of rattlesnakes. Eugene learned how to sneak up on a snake, distract it with his left hand, then grab it by the tail with his right hand and whip it in the air till its head snapped.

White folks on the rez. The OmAHa tribe had a legacy of friendship and trade with the white man throughout the 1800s, and in the early 1900s they were accommodating to white people sharing their land. Wary, but generally accommodating.

- Big John was the first white man Eugene had ever gotten to know. His name was John Gilder, but everyone called him Johnny-tonga (Big John). He was a friendly giant of a man with a handlebar mustache who loved the OmAHa people and did odd jobs for everyone. Eugene befriended him immediately, followed him around like a pup, and learned a lot of simple skills and tricks from the grinning Goliath. Everyone liked Big John, but they were suspicious of him. He was a white man with a white man’s mind. He had the biggest feet Eugene had ever seen. Though Laura wasn’t thrilled with her son’s friendship with this strange white man, she grudgingly accepted it

- The Adairs, on the other hand, were a lazy white family living in a dilapidated, one-room shack across the creek from the Leverings. Both Adair parents and all nine boys chewed tobacco. The mother chewed, spit, and smoked a corncob pipe at the same time. They didn’t have an outhouse, so their yard became something of a minefield. Everyone avoided the Adair family.

- The Johnsons were also Eugene’s neighbors. They leased land from the OmAHa tribe to grow crops and livestock. There were several Johnson boys, but Eugene never got to know either them or the Adair boys. Both white families kept to themselves and showed little interest in the OmAHa people and their customs…

… with the exception of one custom in particular—funerals.

Graveyard races. When someone died on the OmAHa reservation, the family and friends decorated their graves with gifts of gold and silver pieces, money, textiles of silk and calico, beadwork, and smooth, cut-glass dishes filled with fruit, candy, and cake. The gifts, which were placed at the head of the grave after the funeral ceremony, would be taken along to the next life by the spirit of the deceased… unless old man Adair heard the news.

When a funeral procession climbed the hill toward the new grave, Old Man Adair could usually be seen at the far end of the hilltop cemetery, wide-brimmed hillbilly hat in his folded hands, looking like a man simply paying his respects. He observed quietly until the ceremony ended and the mourners left the grave and were over the hill and out of sight. Then he waved his big, dirty hat wildly over his head.

Meanwhile, during the funeral all of the Johnson and Adair boys had gathered at the bottom of the hill on the opposite side, waiting with anticipation. As soon as Old Man Adair raised his hat, all the boys scrambled up the face of the treacherous hill into the cemetery, weaving in and out of crosses and headstones until they reached the embellished gravesite. The fastest runners grabbed the gold, silver, and money, then everything was up for grabs. There was scrabbling, screaming, and shouting amid a blur of arms and legs that sent dishes and candy flying through the air and scattering across the ground, leaving deep footprints in the fresh clay above the new grave.

Big John had mixed feelings about those graveyard races, but at some point he sat Eugene down and said, “You know, Eugene, the stuff is going to be looted sooner or later anyway. You might as well take advantage of the opportunity.” He riveted some baseball cleats onto a pair of old sneakers to give Eugene an edge.

Fortunately, Laura never found out about the treasure chest full of prizes that her son had pirated for Big John.

Exhumation. Big John did a lot of jobs that the OmAHa people found repulsive, such as digging up shallow backyard gravesites and burying the corpses properly in the cemetery. Eugene found the work spooky, occasionally terrifying—like when the grinning corpse he was easing out of the ground suddenly snapped in two and fell back into the hole—but Big John paid him 3 dollars for the work.

When Laura found out, she was appalled. Since her time at Carlisle school, she equated death with disease. She marched her son to the woods, had him build a fire, strip down, and throw his clothes (and the 3 dollars!) into the blaze. She told Big John that if he ever had Eugene do that kind of work again, Big John would no longer be welcome on the Levering property.

Initiation into the OmAHa Circle of Dancers. Like most Lakota infants, Eugene had often been picked up under the arms by uncles who danced the child on their chests. There were even special dance songs designed for infants, “Ko-ko Kay. Ko-ko Kay….” (Little Crazy. Little Crazy….). Since then, dancing had always been a part of his life.

So, in the summer of 1916, at age 10, he was initiated into the OmAHa circle of dancers. For more than a year Laura and her relatives from Pine Ridge had collected handmade and store-bought blankets, beadwork, clothing and countless other items for the big giveaway ceremony. Now a large crowd filled the big brush arbor.

After a lengthy introduction by the eYAHbaha (announcer), Eugene walked to the center of the arbor as a slow, heavy beat started to pound from the big drum made of wood and rawhide, mounted on stanchions next to the chiefs. Eugene began dancing to the beat of the slow war song as it played through the first time. The second time through it picked up tempo, pulsing faster and faster.

The boys and men standing around the side of the arbor began to join in one by one. Before long, the center of the arbor was packed with dancers, and all the women and spectators were pulsating in time with the beat of the fast war song.

Eugene was dancing full speed, elbows back, knees high, keeping time with the beat, and then stopped cleanly on the last beat.

Then came the giveaway. Eugene’s stepfather Levi handed a list of recipients to the eYAHbaha, who called names one by one—old people, guests, tribal leaders, friends, who then approached the relatives and accepted a blanket, a shawl or some beadwork. Each recipient would receive his gift, walk to Eugene, and either give him a slight nod and gentle handclasp or else run his palm downward in front of the boy before holding his palm on his own chest, as if to say, May your honorable qualities become part of me.

Finally, a dozen horses were herded into the arbor. Among the small herd was Eugene’s pony. The boy’s eyes opened wide. He didn’t realize that his beloved pony was in the deal. His mother had bought it from the Miller Brothers’ 101 Ranch during her travels with the show and had given it to Eugene for Christmas one year. The pony was nervous. Eugene bit his bottom lip to keep from crying. Like all Lakota youngsters he’d been taught not to shame his parents, so he held his emotions in check… barely.

Three of the finest horses were separated from the herd, slapped on the rear and sent galloping out of the brush arbor. One of them was Eugene’s pony. These three horses would belong to anyone who could throw a rope around their necks. If several ropes happened to hit the mark, the bottom rope decided the new owner.

The other horses were then given to selected guests or members of the tribe.

Eugene knew the giveaway was important, but his own pony….

>>>>———————————>

07 Indian Schools: ‘Kill the Indian, Preserve the Man’

Pipestone. That fall (1916). Eugene and a dozen other youngsters from the Omaha and Winnebago reservations left the train station at Sioux City and headed nervously to the Indian school at Pipestone, Minnesota. Once the children arrived in the early afternoon, the first step was indoctrination and registration in the small office of JB Davis, school disciplinarian—a big man with a rough face and cold, dark eyes. After a brief speech about strict discipline, JB pointed to a small whipping bench in the corner and a variety of whips hanging on the wall—wide straps with rivets at one end, rubber hoses, a cat-o-nine-tails, and several bull whips, or “black snakes.”

That night, the dormitory was silent and there seemed to be a sense of dread lingering over the boys, most of whom were still awake, waiting. Suddenly a loud crack came from JB’s office followed by a shrill scream. Eugene cringed. Another crack. Another scream. Another, and another. With each blood-curdling duet, Eugene crawled deeper and deeper under the sheets and covered his head.

When the noise ended, Eugene remained tense… waiting… waiting… and eventually fell into a troubled sleep. The next morning, over breakfast, one of the students told him it was routine. When a student ran away from school, bulletins went out to all the surrounding farms. Anyone lucky enough to capture the runaway would receive a $3 bounty. This time the student had been caught in early afternoon and taken to JB’s office for a lecture, then called back after bedtime for the retribution.

Eventually Eugene adjusted to the Pipestone way of life—student gangs, perpetual hunger, stiff corduroy uniforms, itchy union-suit underwear, brass-toed shoes, and platoon formations of students marching everywhere but to the outhouse.

Students had organized into tribal gangs—Lakota, Oneida, Chippewa, Pottawatomie, Arickaree, Sac and Fox, and others. Eugene was Lakota but fell in with the Omaha-Winnebago gang, since he’d come to the school with them. They were the smallest gang. The biggest gang was the Chippewa, since their reservation was nearby.

Years later, Eugene would tell stories of the gang wars that went on, usually over stolen food, since there was never enough food for all the kids, and because the dishes that were served in the cafeteria usually consisted of a few overcooked vegetables and an occasional piece of tough meat alongside a dark, greasy gravy over white bread.

Eugene missed his mom, and one day she finally came to visit. Laura stood outside watching the kids marching in platoons, when one boy broke ranks and ran to her with outstretched arms, crying, “Mother! Mother!” Eugene watched the lucky guy run to his mom but suddenly stop, slump, and turn back toward his platoon. It wasn’t his mom after all.

Then Eugene took a closer look. Wait… that’s my mom!

Eugene looked again to be sure, then he broke ranks and virtually flew to her, screeching to a halt and then gaping when he sensed her hesitation. “Who are you?” she asked Eugene.

Laura didn’t recognize her own son for a moment. His oversized corduroy coat was fastened in the back with a rusty nail, and the lining was stiff from the syrup sandwiches that Eugene smuggled regularly from the mess hall. The clumsy shoes weren’t the same size. The heavy, flannel, union-suit underwear was so small that the shirt section couldn’t be buttoned. His chapped skin looked like alligator hide. It was a common practice of Pipestone students to urinate on their hands to relieve the pain of dry skin. When Eugene walked, he looked like a big bell, his little legs churning inside the stiff, corduroy coat as it swayed back and forth.

Laura was shocked and choked back tears when she realized it was Eugene. She took him out of school for the day, buying him some new clothes and treating him to a nice lunch at a local restaurant as Eugene related gruesome stories about his life at Pipestone.

Laura’s husband was well-known in the Bureau of Indian Affairs, so her visit made waves at the school. Officials initially denied Laura’s charges of cruelty and neglect, but improvements were gradually, grudgingly made at Pipestone. Eugene was quickly promoted to tour guide, one of the lucky kids who dressed nicely and showed visitors around the campus.

After that, Laura was barred from visitations to Pipestone school.

>>>>———————————>

08 Death of Chief American Horse / Sacred Instruments

Special thanks to the American Horse family, especially the Chief’s grandson Joe American Horse (born in 1934), who provided details to fill some holes in this article.

Around 1920, Laura’s daughter died back home on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota, so she divorced Levi Levering and left the OmAHa reservation. She and Eugene settled in a cabin near the Pine Ridge town of Kyle, South Dakota, in the Medicine Root district. It was up to Laura and her son Eugene to take care of his five little cousins, now motherless.

At age 16 he got into the booming fencepost business while barbed wire was slashing scar after scar across the western landscape. Eugene drove a horse-drawn wagon at dawn along the creek to a thicket of ash trees, where he cut poles six ax-handles long… long enough for two fenceposts. In late afternoon he hauled the poles to the general store at Red Rock, South Dakota, and traded them for food and clothing.

Heading home around nightfall on crisp, winter evenings, the wagon bed loaded down with groceries, Eugene was lulled by the rattling of stanchion chains, the jangling of small harness chains, and the clip-clop of the shod, trotting horses. Dogs barked as his percussive music floated along the dark, frozen creek.

Around that time, their neighbor Chief American Horse was an old man… a venerable leader of his people with waning responsibilities and a weary heart from the injustices that he and his people had endured.

Eugene recalled the morning when the chief’s son Ben American Horse and his friend stopped by for a visit. Ben was a policeman on the reservation. He’d been one of the first students at Carlisle Indian school and a Wild Wester (like Eugene’s father, Luther Standing Bear). Now Ben stood six-foot-six, all bone and muscle. He packed a pair of pistols with notches carved all over the handles. Ben’s best friend was his brother-in-law, Ben Chief, another larger-than-life Lakota man. The two big Bens were often seen together on the reservation, an imposing sight.

Early one winter morning in 1922 the two Bens climbed into their old Ford truck and drove through a blizzard to tell neighbors that Chief American Horse had died. Entering Eugene’s cabin in mid-afternoon, they removed their heavy fur coats, shook the snow off, and told Eugene’s mother the news. The three began mourning—crying hard for about 30 minutes. The five youngsters gathered close around Eugene, who wrapped his arms around them as a cleansing sadness settled over the house.

After the cry, Ben American Horse told Laura that his family would like Eugene to build a casket for the burial. “Eugene has been to school and has learned much. We know he can do this.”

It was a great honor for Eugene. He climbed into the truck with the two Bens, went to town for the materials to build a casket, and returned to the American Horse farm. The chief had been laid in a small log cabin near the main house. Eugene measured his height and shoulder size with a string, then was driven across a bridge over the creek to a large cabin where the casket would be built.

Meanwhile, friends and neighbors had gathered from miles around. They cleared away the two-foot snowdrifts from around the house and erected their wall tents. By nightfall Eugene was busy working across the creek from the mourners, who were singing Christian hymns translated into Lakota. Most of them could read Lakota, but not English.

In the dark hours of early morning the casket was completed under the close supervision of Ben American Horse. Eugene hauled the casket outside while Ben shouted the news to the mourners across the creek. Six young men mounted up and nudged their horses to a trot toward the cabin. As they approached, Eugene could only see the bouncing orange embers of the Bull Durham cigarettes dangling from their lips. An eerie sight… like a squadron of dancing fireflies.

The riders lined up on either side of the casket and removed the ropes from their saddles. Ben slipped the ends of the ropes through the casket handles and returned them to the riders, who hoisted the casket, wrapped their ropes around their saddle horns, and moved in slow formation back over the bridge to the small cabin where Chief American Horse lay at rest.

Eugene was asked to help Ben change the chief into his buckskin clothes. He’d died wearing a pair of gray Levis and an old blue shirt, looking to Eugene like an eagle that had been plucked and painted. Removing the clothes from the stiff body revealed thick, heavy ridges of scar tissue on both arms and legs and across the chest and stomach.

It wasn’t unusual to see Lakota leaders with scars in the early 1900s, whether from battles against the cavalry and warring clans in the previous century, from Sun Dance ceremonies, or from slashing their arms and torsos as a sign of sacrifice for their suffering people.

They managed to dress the chief in a good set of his buckskins.

Early the next morning, a few hours before the mourners would begin to form a mile-long procession that would move slowly from the American Horse home to the American Horse church beside the cemetery, Eugene drove a wagon to the cemetery and picked through eight inches of frozen topsoil before reaching the soft clay below. He and three other men dug quickly in shifts and finished the grave.

By the time they finished digging and entered the church, the service was nearly over, so Eugene quietly found a seat at the back of the room. Ben American Horse was standing in the pulpit thanking friends and relatives who had come to mourn for his father. Other family members sat nearby, next to trunks loaded with goods to be given away. Ben finished the eulogy, and hundreds of family possessions were given to relatives and close friends.

One of the last items was the chief’s bundle of dancing clothes. There were a few gasps and some surprised expressions, since dancing clothes and their sacred instruments were usually kept in the family. Eugene was stunned when Ben said, “Eugene has been of great help today. He will have our father’s dancing clothes. He is one of the best dancers on the reservation. He is right for this gift.”

Eugene approached the American Horse family and accepted the gift with awe… as well as some trepidation. Owning these things would be a great responsibility. Returning to his seat at the back of the room, he peeked inside the bundle. It contained beaded moccasins, fur leggings, eagle feathers, a roach, arm bands, and cuffs. There were several sets of bells, both the metal type and the traditional deer-toe clackers. Also in the bundle was an eagle-bone whistle, a sacred, finely polished instrument used by prophets and medicine men during special ceremonies. The whistle alone was one of the greatest honors a 16-year-old Lakota boy could imagine.

Eugene spent the evening feasting and visiting with friends before walking home that night. He hadn’t slept for nearly two days, and he felt like he was in a trance. It was a strange winter night anyway. Something was present in the still, dark air that he could only sense, and he started his journey with an uneasy feeling, as though he was being followed and watched. He carried the big medicine bundle over his shoulder. Off in the distance, a mile away he could see the dim glow from the lamp his mother always hung in the window at night.

As the sounds of the funeral party faded and disappeared, the only sounds now were Eugene’s muffled footsteps on the snow-covered path and the occasional barking of dogs, who also seemed to sense the strange energy in the winter air.

Eugene couldn’t take his mind off the sacred bundle, especially the eagle-bone whistle. Halfway home, he gave in to an overpowering urge to open the bundle and dig out the sacred whistle. He stopped and studied it in the moonlight. He knew it should be used only in special ceremonies, but he couldn’t resist. He brought it to his lips and blew. The shrill note split the night… then all was still. Even the dogs fell silent.

As Eugene quickly replaced the whistle and closed up the bundle, a sudden gust of wind rustled a patch of tall grass jutting up through the snow just ahead of him… and he froze.

The gust swept toward him, disturbing all of the clumps of grass around him, then it circled and hit him from behind, making his pant-legs flutter… and he began to walk quickly.

The gust swept around him in a circle and hit him again from behind… and he broke into a trot.

Again and again, like a whirlwind, the gust created circles in the grass and kept pushing Eugene toward home as he dashed the last half-mile.

He stormed through the yard and grabbed the door latch. As usual, it was locked, so he pounded on the door and waited desperately for his mother to open it. A few seconds seemed like an hour as the wind swept the front of the cabin and crowded the boy against the doorway.

He launched himself from the porch and dashed one lap around the cabin, returning just in time to see a sliver of light cut through the darkness as the door opened. He dove into the kitchen, landing on his hands and knees as the bundle went sliding across the floor.

Laura stood gaping at her son, shaking her head. “Hoo-hee, hoo-hee, hoo-hee” (My goodness!)

Eugene climbed shakily to his feet while Laura picked up the bundle of dancing clothes and inspected it with wonder and a bit of reverence. Eugene told her about the whistle and the wind, and he felt a little ashamed as she said calmly, “It’s okay, Son, the Chief was just protecting his sacred bundle.”

She told Eugene to go to the barn and get the longest teepee pole while she fixed a plate of fry bread, meat, and soup in the kitchen. When her son returned to the house, she tied all the clothes and instruments to the narrow end of the pole, took the plate of food, and accompanied her son to the hitching post, where they lashed the pole tightly like a flagpole so that the sacred belongings of Chief American Horse waved high in the night sky. She laid the plate of food at the base of the pole as an offering to the chief’s spirit. They stood together in the dark while Laura spoke in Lakota to Chief American Horse.

“Help us. Be patient and helpful with the boy. He’s young and doesn’t understand everything yet….”

(In the old days, a young man would have stopped in his tracks when a spirit was trying to communicate. He would have spoken aloud in prayer to the spirit.)

“… we’re struggling and poor. It is a great honor the boy received today. Be patient. He will live up to the honor. We’re sorry you left us, but you’re up there with the great people now. We offer you this food and these sacred clothes tonight. Please accept this offering….”

The next day the sacred bundle belonged to Eugene for life.

>>>>———————————>

09 Honky-Tonk, Rodeos, and Sports

It was the Roaring 20s, and big cities were letting off steam with jazz, flappers, the Charleston, and bathtub gin, while out west it was honky-tonk, polka, beer, and rodeos. Uncle Sam had been through the first world war, and now he just wanted to have fun.

In the summers, when Eugene wasn’t at school, he was finding fun ways to make a living.

Honky-tonk. In 1922 he started playing drums in a band. With a drum rack welded onto the back of his Model-T touring car, he left the reservation with a six-man crew of Lakota musicians to ride the honky-tonk circuit along the Nebraska border (Chadron to Martin to Sparks…) and badlands towns up north, like Interior and Wall. They played the popular pre-blues, hillbilly, and novelty songs of the 20s.

“Honky-tonk” can refer to a western bar that plays western music, or to the western music itself, or to a poorly maintained instrument like an old, out-of-tune piano used to play it.

The leader of the band was Eddy Coutier, a young Lakota who’d lost his right leg in the war. When he stomped four beats with his wooden leg to start a song, the whole stage shook.

Boom! Boom! Boom! Boom!

“It ain’t gonna’ rain no more, no more, it ain’t gonna rain no more.

How the heck can I wash my neck if it ain’t gonna rain no more….”

Or…

Boom! Boom! Boom! Boom!

“Yes, we have no bananas, we have no bananas today.

We’ve string beans, and onions, cabbages, and scallions…”

The band usually sang the second chorus in Lakota. They were a half-dozen fun-loving musicians on sax, trumpet, guitar, trombone, drums, and piano… and there were plenty of gigs. Farmers, ranchers, cowboys, and their wives and girlfriends filled the large dance halls on the weekends, and the dance floors were crowded. They brought over free drinks for the musicians.

More refined orchestras came through the area with good string sections, but they didn’t go over as well in the Dakotas as they did back east. People here wanted hot, honky-tonk dancing music…

Until a stranger came to town.

“Did you get Chadron?” the boys would ask Eddy.

“Naw, that polka band got it, with the guy that pumps accordion.”

The accordionist was a German immigrant called Lawrence Welk, who grew up in the Dakotas speaking only German, and in 1924 started playing with some small touring bands (Luke Witkowski, Lincoln Boulds, George Tucker) before starting his own bands and orchestras and eventually getting famous for his own style of “champagne music.” But, for now, he was into polka, played on the accordion with a back-up band. Polka, like honky-tonk, let the rough crowds laugh and lighten up despite themselves. It probably helped ease the leftover tensions and prejudices against Indians (from the 19th Century) and against Germans (from the first world war).

Rodeo clown. After playing in the band all night, Eugene would sometimes rustle up a job the next day as a rodeo clown dressed in long, flapping tennis shoes, a red wig, red rubber-ball nose, and baggy overalls held at the armpits by short suspenders. He’d ride a bucking jackass or paw and snort face-go-face with an angry bull that was reluctant to return to the gates after a wild ride.

In the summer of 1922, he clowned at the Martin Fair and Rodeo in South Dakota. One afternoon he scanned the faces in the stands and recognized one of the baritone players as John “Artie” Artichoker, a top athlete from the Winnebago tribe who’d excelled at two top Indian Universities—Haskell and Carlisle, where he’d played football with the famous Jim Thorpe. Artie had a versatility of music and athletics that was common among Plains Indian men and women. Artie had also noticed Eugene’s antics out in the arena throughout the day and was maybe a little impressed by his fitness and agility.

Eugene decided to have some fun with the band. He stood on the dirt track facing the musicians, swinging his arms in exaggerated arcs to mimic a band director. He didn’t realize that a group of runners had lined up behind him for a foot race around the half-mile track… and the crack of the starting gun sent him flying into the stands and sprawling at the feet of the musicians.

Artie Artichoker broke out laughing and shouted, “Hey! Clown! Let’s see you beat those guys!”

Eugene jumped to his feet and gave chase. Despite his flapping shoes, he caught up to the pack halfway through the first turn and began zigzagging in the outside lanes alongside the Lakota runners. Occasionally he jumped three feet in the air like a scared antelope. In the stretch he pulled up alongside the two lead runners and matched them stride for stride.

“Hey!” Eugene shouted with just a hint of a pant. “What’re you guys chasin’… rabbits?”

The runners didn’t seem to be enjoying his show. One panted to the others, “Ignore him. He’s a clown; he’ll quit pretty soon.”

Eugene chuckled. “Well, good luck, fellas. I’m goin’ home now.”

As they approached the last turn, Eugene opened up and slowly pulled ahead of the pack. With a 30-yard lead he tumbled to the ground just before the finish line.

The stands of predominantly Lakota spectators went wild and stomped their feet. “Get up, Clown! Get up!”

But Eugene just lay there, motionless, watching the runners approach. Twenty yards. Ten. Five….

Seconds before they reached the line, Eugene flopped his leg over to win the race.

Later that day, Artie Artichoker introduced himself to Eugene, who’d get the surprise of his life later that summer. After the rodeo, Artie sent a letter to Dick Hanley, the new football and track coach at Haskell Indian University, to recommend Eugene for a scholarship. Hanley was a young ex-marine and serious college coach who heeded the advice of his graduates, especially the top athletes. So, against all odds (there was a long waiting list to get into Haskell), Eugene received a letter offering him a full scholarship in the fall of 1922.

College track star. At the time Eugene enrolled at Haskell, the school was putting out some of the finest athletes in the world. Their nonconference football team, the Fighting Indians from Lawrence, Kansas, toured the country to play against Yale, Harvard, and other college teams from Minnesota, Nebraska, Texas, California…. They had an all-American fullback, John Levi, who could throw the ball goalpost to goalpost, and an all-American tackle, Theodore “Tiny” Roebuck, who in one game pushed a California team all the way back from mid-field in three plays to score a touchback for Haskell.

Haskell didn’t host football games because the school didn’t have a stadium until 1926, the year Eugene graduated… but that stadium is another great story that ties into Eugene’s charmed life (… a sort of Native American Forrest Gump).

But at 5’11, Eugene wasn’t invited to Haskell for football. Coach Hanley had him earmarked for decathlon events, especially running the 100-meter dash, 400-meter dash, 1,500-meter run, and relay races.

When track season started, Eugene found serious competition for the first time in his life. Lawrence White Bird was half Cheyenne, half Lakota, and became Eugene’s best friend and toughest competitor at Haskell. In short runs (50-yard dash or half-mile sprint) White Bird usually won. But in mid-distance speed pick-ups like the 300-yard stride it was Standing Bear who usually broke the string. Other top runners at Haskell in the early 1920s were Winfred Bland (Creek) and Wallace Little Finger (also called “Yellow Horse”… Lakota).

Like Notre Dame, the Haskell track team was nonconference but well-known. Coaches knew they’d get stiff competition from the student athletes from Lawrence, Kansas, so schools from around the country invited Eugene’s team to track meets, and they invariably returned to campus with some first-place awards.

.

>>>>——– Eugene’s Life in a Nutshell ——–>

.

So far we’ve seen the first half of his life (above), which could be split up into 10-year periods:

- 1906-16 – Growing up on the reservation, learning Lakota traditions, watching intertribal tensions grudgingly melt, and feeling the relentless pressure of white civilization.

- 1916-26 –Attending Indian schools that were sometimes kind, sometimes brutal… but always intent on overhauling native students with skills and ways of the new America.

- 1926-36 – Getting married and living not just the good life, but the gatsby life among the richest of the rich… becoming a golf champ, touring the country in a fleet of limousines, and finding himself among CEOs and Presidents.

Now we look at the second half of his life (below):

- 1936-46 – Divorcing his wife Mary, leaving the wealthy Osage tribe, and tumbling into two grueling years in tough mining towns, then soaring into a prosperous maiselly marriage, building a 5-star restaurant, and enjoying the rugged life of a commercial fisherman… the subject of the next chapter.

- 1946-1960 – Sliding down to “skid row.”

- 1960-1980 – Surviving the ravages of alcoholism, going into recovery, and returning to his heritage, while immortalizing the lives and personalities of his people through his artwork.

.

>>>>———————————>

10 Loose Ends and New Beginnings

Oklahoma mining. In the mid-1930s, at the height of the Great Depression, Eugene’s restlessness and heavy drinking took a toll on his family, so he got divorced and left the Osage reservation in 1937. Jobs were scarce, but lead and zinc mines were flourishing. Most of the bullets fired by American soldiers in the two world wars were forged with lead from the mines at Picher, Oklahoma, located about 70 miles east of his former Pawhuska mansion as the eagle flies. America was now between those two wars, and lead was pouring out of those Picher mines, so Eugene became a miner.

After drilling all day, he trudged back to town in the evening with short, heavy steps. He rented a room upstairs above one of the local taverns. As he came through the front door of the tavern, the bartender reached under the bar, grabbed a pint bottle of whiskey, and slapped it on the bar top. Eugene grabbed it on the way to his room while the bartender marked it on his tab. All the miners living upstairs were offered the same service. Drudgery and alcohol were the work-a-day routine of most miners—men of muscle and bone who could cut calluses off their hands with a knife.