(Among the adjustments the Lakota people had to make in the 19th and early 20th Centuries were clocks and calendars. It was part of their culture to move with the flow of life in North America, oblivious to dates and times. Moving among the lakes and rivers on the Plains meant adapting to nature’s seasonal changes. The old year ended and the new year began with the first snowfall. Simple. All of those Euroamerican measurements probably seemed a bit fussy… much ado about nothing. So while I trust the basic storyline of Gene’s family life as he told it to me, a few details, especially the time-related ones, have caused me to do some scrambling on the Internet, where I find some inconsistencies. I add a brief note at those uncertain points along the way. MM)

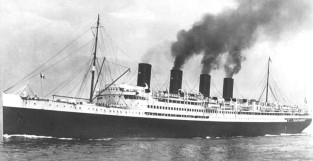

When I met Eugene Standingbear around 1977, a few years before his death, his most vivid childhood memories included riding with his mom on a steamship to Europe (possibly in 1908), in the Miller Brothers 101 Wild West Show. The Lakota boys were enchanted by the masts and rigging lines. Eugene was too young to climb very high, but he watched in awe (and the moms watched nervously) as older kids scrambled up high above the deck and did brave antics.

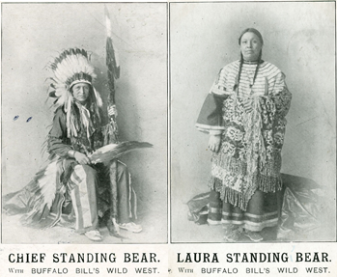

Eugene’s mother Laura told him exciting stories about her similar travels with his father, Luther Standing Bear. Laura and Luther had met at the Carlisle school, and like a lot of other Carlisle graduates from the Lakota tribe, they were eventually drawn to the adventure, travel, and good pay in the wildly popular Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. Luther joined up in 1902 as a horseback rider, dancer, interpreter, and chaperone for the 75 Indian members of the crew (more about this in a later article). The job lasted until one foggy April morning in 1904, when he and two fellow cast members were on their way to England to meet up with the show, and their train was rear-ended by another train in Melrose Park, Illinois. They were in the last coach car, which was demolished. Luther was broken up badly and nearly died. When he returned home to the reservation in 1905 to convalesce, he was chosen as a tribal chief and honored with a big celebration. Laura and Luther were together by this time, and they gave away all of their possessions during the ceremony.

The year 1905 was also probably the year Eugene was conceived. Though historical accounts on the Internet often list his birth as “c. 1900,” Eugene told me he was born March 7, 1906, and I suspect he was right. Luther says in his books that the train wreck happened in 1903, while newspaper accounts say it happened in 1904. Maybe times and dates aren’t really so important in the big picture. Time is illusory, as I’m sure the Great Mystery and the spirits would agree. 🙂 In any case it was a difficult time for Luther, who soon decided he could do more for his people by finding a place in white society from which to enlighten the public about the real Native American people and their noble traditions.

Most Native Americans were not considered US citizens at that time and were compelled to live on reservations. Luther was given US citizenship status in 1907, allowing him to move off the reservation, leaving his wife Laura and son Eugene at Pine Ridge. Laura would continue traveling with the wild west shows, bringing Eugene along on one trip in 1908.

By 1908, with international tensions building in Europe leading toward the first world war, and with the coming of motion pictures, the many wild west shows (1870-1920), which had been all the rage, were now losing their luster… so Laura and her son Eugene eventually returned home to the Rosebud and Pine Ridge reservations in South Dakota.

Uncle White Bull

While Laura was finding her way as a single mother, she often left Eugene with the family of her brother, Eugene’s Uncle White Bull #2, a full-blood Lakota who lived with his wife Emma and their two sons, Levi and Martin, at Porcupine district on the Pine Ridge reservation. Porcupine station had a post office, general store, and Indian ration house that received monthly army rations (food, blankets, clothes, and hobnail shoes mass-produced for the first world war) that were distributed to reservation families who needed them. The store was in a valley beside a creek between ridges topped with pine and cedar trees.

Less than a mile away was Porcupine Butte, where White Bull and other grown-ups would occasionally venture alone to commune with the Great Mystery. Three or four days of fasting and meditative daydreaming often brought visions of spirits of ancestors or birds or animals. It was a big deal when one of the tribe’s holy men climbed the butte to give thanks for mercy and for the gifts of life, and to ask for protection for the people. After three or four days two young men would climb the butte, locate the holy man, and escort him home, and if he learned something important, he’d call the other leaders together and describe his visions. They could follow the dictates of the messages if they wanted to.

White Bull sometimes told Eugene about the spirits he could see from the corners of his eyes. “They move very fast, and by the time you turn your head to look at them, they’re gone.” He could speak to the spirits, and they sometimes answered silently in his mind. Or they might answer through the wind or through the actions or sounds of birds and animals.

White Bull and white culture didn’t get along. He never took the time to learn English, and he refused to hear the words of Christianity, even when spoken in Lakota. Father Luther was a white Catholic priest who took his job so seriously that come rain, hail, dust, or subzero blizzard he could be seen driving his buggy across Pine Ridge. Several times he was found in his buggy, stranded in a blizzard, nearly frozen to death, and a Lakota rider would have to guide his team to the nearest farm, but probably not the White Bull farm. White Bull thought it best to ignore a strange white preacher who was apparently suicidal.

Many Lakota children were sent away to bible schools like Santee, where religious stories were drummed into their heads before they were sent back home to the reservations a few years later as Christian missionaries. White Bull had seen their diagrams of heavenly stairways to the clouds and dark paths littered with whiskey bottles leading to the devil. He didn’t believe in a devil and he didn’t drink alcohol. Period. He’d seen his people coerced to their knees before the cross, but warriors like White Bull kneeled to no one. So he didn’t let those reservation missionaries come to his home, despite their determined (sometimes strange) efforts to visit him.

Only a few of the many Lakota kids who attended Santee actually took the calling to become missionaries once they returned home… and one of those eager young men was determined to convert the stubborn White Bull. One summer evening he sneaked through the woods and hid behind a tree 200 yards away. He draped a white sheet over his head and shouted at the White Bull cabin in a ghostly wail in Lakota, “Hey, White Bull. Whi-i-i-i-ite Bul-l-l-l-l….”

White Bull grabbed his rifle from above the front door, poked his head out the window, and bellowed, “Who are you?”

“I am Jay-y-y-sos-s-s, son of Wakan Tanka-a-a. I’ve come to talk with you, show you a new life. A great life!”

“Go away! I don’t want you coming here.”

“I am coming, prepare to meet the great one.”

White Bull saw the suspicious tips of the white sheet moving on either side of the tree trunk, then the strange figure stepped out from behind the tree. “Here I come! Humble yourself. Get down on your knees?”

Well, that was too much. White Bull raised the rifle, aimed, and shot the tree,… CRACK!… sending pieces of wood and bark flying everywhere.

The terrified missionary bolted back behind the tree. White Bull reloaded, aimed, and fired again… CRACK!... hitting the ground inches from the base of the tree, scattering dirt into the air and onto the sheet.

“Hey! Don’t shoot! It’s me!” yelled the missionary.

White Bull fired again… CRACK!… hitting the base of the tree trunk, and the ghost figure fled.

>>>—–>

White Bull was 6’8 (203 cm), well-muscled, and an expert with spear and bow and arrow. Before an exhibition, he’d practice by firing arrows between the feet of his son Levi, who would be walking around his dad in a 40-foot-radius circle. White Bull would aim, fire, and hit accurately between the feet of his walking son.

He took occasional trips to the west coast, visiting tribes along the way, trading with them, and learning their languages.

He cleverly taught his sons and Eugene the sign language that was common to all Plains Indians. Many evenings the three kids would ask him to tell one of his many stories, and his hands would sign smoothly as he narrated Disney-like fairy tales about animals, spirits, the plains landscape, and the Lakota people. White Bull’s voice would change from brave to ominous during the scary parts. His face would reflect awe during the beautiful scenes, and the children would cry when he told the sad parts. At the end of the story, one word, ha-chip, would seal the children’s lips. They knew they should not speak anymore and it was time to go to sleep.

>>>—–>

A Lakota lodge looked similar to this Seneca-Iroquois longhouse, but with log walls extending about 200 feet. Sorry, I couldn’t find a picture of an old Lakota lodge.

Throughout the year the families would gather on special occasions in one of the rough and sturdy lodges—either a longhouse building or one of the large, roundish, six-sided structures, all made with logs—to treat neighboring districts to an evening of feasting and dancing. Gene admired how White Bull and his wife prepared for the celebration, dressed up in their finest dancing clothes, and readied their sons Levi and Martin. First thing in the morning, Aunt White Bull started a fire under a large kettle of dried meat with wild turnips to simmer all morning for the potluck celebration and dance, which would begin around 2pm.

Meanwhile his aunt and uncle got dressed up. She put on a broad-cloth dress decorated with elk teeth (only the front teeth of bull elk), and a wide concho belt with string tapering down the side of the hips. A wide ribbon with a large bow tied behind her neck had two long streamers hanging down. She wore broadcloth leggings and beaded mocassins. Eugene thought she was stunning… beautiful.

Uncle White Bull put on an Indian calico shirt and a leather belt to hold up his broadcloth loincloth and plain buckskin leggings, with short fringes down the sides. He wore a braided sash of pretty designs over his shirt and a braided strip around his waist. During the day he’d wear his wide-brimmed reservation hat with high, tapering crown. Sometimes he’d tie a handkerchief around the hat and tuck in an eagle feather with its black tip pointing straight back. In his hand he carried his long pipe in his tobacco pouch.

Then Uncle and Aunt White Bull would help each other with final preparations. She would braid his hair using tallow grease melted down with fragrant herbs, maybe sage or peppermint. Then he had his wife sit down so he could stroke her hair into good shape with a porcupine-tail comb. He’d part it exactly in the center of her head, then apply face paint made from berry dyes and clays mixed with tallow to form a paste. The desired effect included red cheeks, a red part in her hair, and specific markings on her chin and forehead.

Traditionally, each person had his or her own paint and colors and designs, and upon death, a holy man would decorate the body appropriately so they could take their colors along to the next life. The family would then give the holy man gifts of robes, headwear, or even a horse.

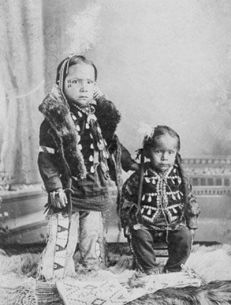

Levi and Martin would strip and put on beaded moccasins with fur around the ankles, then bells above the ankles and below the knees. A leather belt held up the loincloth, front and back, along with a decorated feather bustle in back, and two trailing strands with decorative feathers. On the side of the belt were strips of leather hanging down nearly to the ground, tapered to a point and decorated with large, shiny silver or nickel studs. The boys’ chests would be covered by a bone breastplate or beaded vest or yoke of fine fur such as otter with small mirrors sewn on. The boys’ long hair, either braided or hanging loose, spilled out over a beaded neck-choker. The head piece was made of porcupine longhair and deer tail hair and bore the ultimate Plains Indian symbol: two eagle feathers in the center pointing straight up in reverence to the eagle, the highest and sharpest of creatures on Earth. White Bull carefully painted each of his son’s unique, personal designs on their faces and torsos. Levi wore brass arm bands and bracelets and carried a rawhide gourd with an eagle feather tied to the tip.

After a couple of years the White Bull family started dressing Eugene up for these tribal celebrations too.

Later in life Eugene would visit powwow celebrations and feel a sense of loss when the young people would cover themselves completely up with feathers of all kinds and colors, wear thick angora hair leggings and headwear blended from multiple tribes… “like Greek folk dancers wearing Japanese costumes,” he’d say. It felt as though the old ways were getting buried. He had to admit, though, that when he was a child, many of the old full-bloods probably felt the same sense of loss when tribal members in the 1910s and 20s used bells instead of deer-hoof clackers… colorful glass beads instead of quills, plant seeds, and stones.

“Progress is a big steamroller,” Eugene would say wistfully.

>>>—–>

Like most of the other old full-bloods, Uncle White Bull was a warrior, not a holy man. He had an eagle-wing fan that he sometimes carried and used in dances to fan himself, unlike the holy men themselves, who had their eagle-wing fans with them much of the time to help guide the flow of spiritual energy in the tribe. White Bull’s most important and sacred belongings—his fan, his double-trail war bonnet, his beaded buckskin war shirt and leggings and moccasins—he carried with him to celebrations in two large rawhide bags, like suitcases. The leggings were beautifully beaded with long fringes. When he danced he kept his knees high and his elbows back as he leaned forward. Eugene thought he was a magnificent sight. White Bull didn’t want to taint the dignity of his dancing clothes with bells, so he let the other men keep the beat. Dancers traditionally wore deer-hoof clackers, or “deer toes,” which cast a mellow, mystical aura over a crowded dance floor. The more modern bells were louder, brighter, and produced a more intense, almost intrusive atmosphere… but they could certainly keep the beat.

So the celebration started that day around 2 pm with a speech or two by tribal leaders, followed by the chief’s song. Then many different songs were sung, and the dancing went into full swing. Throughout the afternoon the dancing would be interrupted by giveaway ceremonies, when gifts would be given to visitors and friends. It was a mark of honor to give someone a gift, and an honor to receive it.

In the course of our friendship, Eugene gave me two eagle feathers, and I felt deeply honored. It was illegal for non-Native Americans to own eagle feathers unless received as a gift from a Native American. When he died a few years later, in 1980, I was living in Billings, Montana, writing specs for a database management system for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and a secretary, a young Crow woman, had her mother do beautiful beadwork on the quills of the two feathers. They presented them to me at their home over a dinner of fry bread, a Plains Indian treat, which I’d told her I’d never had the pleasure to taste. Another great honor. Interestingly, I still see the pretty face of the secretary clearly in my mind though her name has escaped me and is trying to fight its way back as I write this, even though I vividly recall the names and faces of the kind, soft-spoken, bright married couple who were computer programmers on the project—Henry and Grace Monarco… he an Apache, she a Navaho. Funny how memories stay with us and play in our mind. Anyway, before he died, Eugene also offered me one of his paintings of the Lakota life in the old days. I was young, single, and moving around a lot, so I had no place to keep the painting and wouldn’t be able to treat it with the respect it deserved… so I declined for reasons of practicality. Eugene expressed no emotion, though I suspect I had dishonored him. Sad how lack of understanding among cultures can cause pain. One of life’s regrets that still makes me uneasy when I think about it.

On a lighter note, Eugene had his life regrets, too. While living with the White Bull family, he and a friend of his developed an arrangement over the years. At one of these tribal celebrations, Eugene would give his friend an imaginary horse during the ceremony, and at the next celebration the friend would give it back. This went on for several years, until the elders caught on and gave the two boys a serious tongue-lashing about pretending to do honorable things… and they had to quit using that poor, virtual horse as a mark of honor.

Meanwhile, back to the evening of the feast on Pine Ridge, the food had been heating up outside all afternoon, and after a couple of hours of dancing it was brought in. Two of the best fancy dancers were selected to do the pot dance to introduce the first course: Pispiza (prairie dog) stew. Each dancer was given a forked willow stick. As a special song was sung, both dancers would dip their willow sticks into the pot and come out with a prairie dog head, which they’d give to the oldest man, who had the seat of honor in the front row. Sometimes it was uncertain who was oldest, since no one had kept track of birth dates in the early 1800s, so the special song might be sung several times while prairie dog heads were served to several old men in the front row. Then the music stopped and everyone joined the feast of many courses using their own plates and cups, which they’d brought along to the celebration.

After the feast, some people returned to their tents to lie down and rest before the dancing, which would continue until sunrise. The most grueling part of the evening for the men was the longdance. The dancers didn’t know when the longdance would begin—the head singer decided—but once it started, the dancers had to keep dancing. Sometimes the doors of the lodge would be bolted so no one could enter or escape during the longdance. Sometimes Eugene would get so exhausted that he wanted to drop… but he kept on dancing. If someone quit dancing and sat down, the whip man, or sergeant at arms, would come over and give him a few hard licks with his bone-handle whip with braided wrist loop and rawhide strand, or “fall.” The intent was not to punish or seriously hurt the young man, but to bring shame—a loss of honor and respect. It was important to keep dancing in order to show your manhood and to protect the family reputation. There was a lot of honor tied up in the war dance. Most of the dancers knew most of the songs, and it was important to make the right moves and to stop on the right beat, lest you earn lots of snickering up blanket sleeves. Visitors from other tribes who didn’t know a song would sit out, and the whip man didn’t bother them. The long dance wouldn’t end until someone finally gave away a cow or a horse to stop it, but no one made that gesture until late into the dance.

Over the years Eugene won several awards for his excellent dancing skills.

>>>—–>

Eugene recalled that most of the men in his tribe were like his uncle White Bull… men of honor who respected the ways of their people. They were honest, forthright, patient, dependable, and proud of their perseverance.

Later on Eugene would leave the reservation and find that living in a modern society was different. Noble values didn’t play such an important role. He’d say, “I met a lot of big shots, but usually you could dot that o.”

>>>—–>

Eugene’s mom, Laura (Cloud Shield) Standing Bear, enjoyed visiting schoolhood friends on other reservations and taking months-long trips with the wild west shows. In the early years, when Eugene was still too young to travel with her, he stayed with the White Bull family, and throughout his life it felt like he had three parents—the White Bull couple and Laura.

Between her travels, Laura, too, lived with the White Bull family. Native American relationships were a step closer than they were among white people. Friends were like cousins, cousins were like brothers and sisters, and immediate family members were almost like a part of oneself. So Laura and Eugene fit right in with the White Bull family.

But like any family, there was some dysfunction. Laura had been to the Carlisle school where she’d learned English, she’d made friends with Native Americans from many tribes, and she’d learned about America’s cultural preoccupations such as sanitary practices and Christian rites… so she and her brother White Bull didn’t always see eye to eye on things.

White Bull told the children stories about the way it used to be, describing the territorial skirmishes between two Native American bands, the buffalo hunts, and the fierce battles between the united tribes and the US cavalry regiments. He used beef steers to show the kids how to properly butcher a buffalo, and how to enjoy a Lakota delicacy—raw kidney and stomach muscle, or “book,” washed and salted.

Laura accepted the stories of valor, but she balked at traditional practices that she’d learned were dirty and carried disease… like eating raw meat.

Levi and Martin had never been baptized. White Bull wouldn’t permit it.

Oh-oh.

One day Laura convinced Mrs White Bull of the importance of baptism, and they decided to have the boys baptized on the sly. While White Bull was gone one afternoon, the two women sneaked Father Luther to the farm to give the two kids the holy key to heaven. The priest spoke several phrases and rubbed the boys foreheads with a cotton swab soaked in holy water.

Timing could’ve been better, though. As Father Luther drove away in his buggy, White Bull came riding into the front yard on horseback, dismounted, and watched suspiciously as the Christian buggy rolled away over the hill. He walked sternly into the front door and confronted the two women, Laura in particular. Whatever had transpired, it was probably his sister’s doing.

“What happened here?” White Bull demanded.

Laura jutted out her chin, narrowed her eyes, and said, “Levi and Martin have been baptized.”

“What does that mean?! What did that man do to my sons?!”

Defensive but confident, Laura responded that the boys had had holy water rubbed on their foreheads. It was important for the boys to get to heaven.

White Bull bellowed at his sons, who were sitting at the table with wide eyes, “Lie down in that bed! Levi, you first.” He stormed to the counter, grabbed a bar of soap, a rag, and a basin of water. He vigorously scrubbed Levi’s forehead with the soapy rag, then did it again to his younger brother Martin.

“There! You’re okay now,” White Bull began to relax. “I’ve washed away all the bad magic.”

Laura scoffed, “You old fool, you can’t wash it away. It’s already done.”

White Bull ignored her. He was satisfied.

(Next up: Life Among the OmAhas….)